On January 11, 2018, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a State Medicaid Director Letter providing new guidance for Section 1115 waiver proposals that would impose work requirements (referred to as community engagement) in Medicaid as a condition of eligibility. As of June 2018, CMS has approved such work requirements in 4 states: Kentucky, Indiana, Arkansas and New Hampshire. A number of other states have waivers pending at CMS to impose work requirements or are considering such proposals. Not all states are interested in Medicaid work requirements, but Senate proposals and the House Budget Resolution passed by the House Budget Committee are calling for a federal requirement that all states implement work requirements in Medicaid.

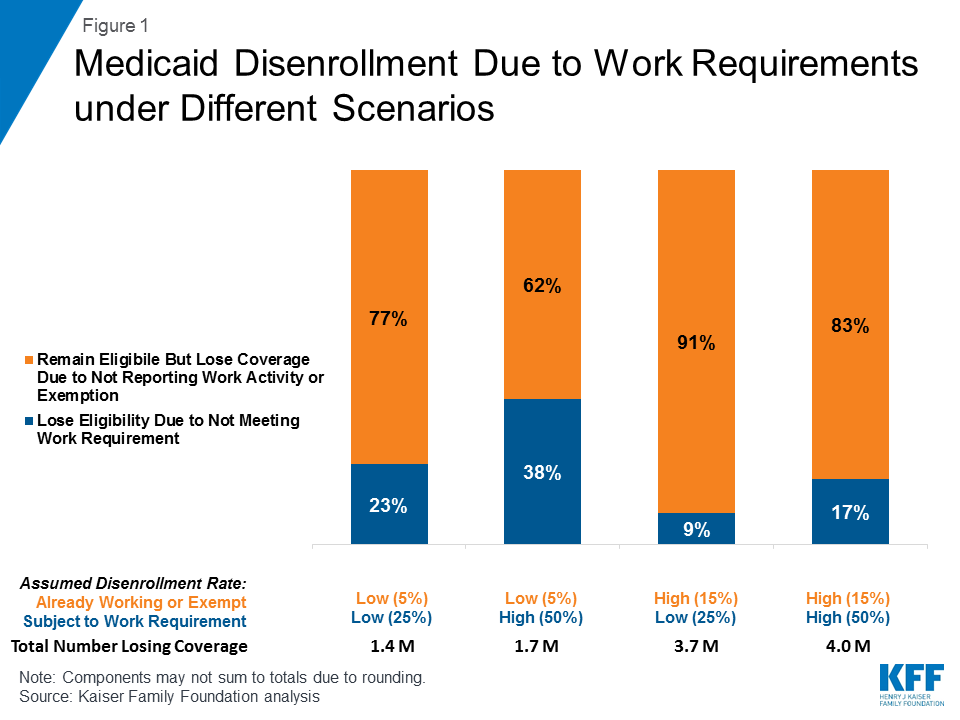

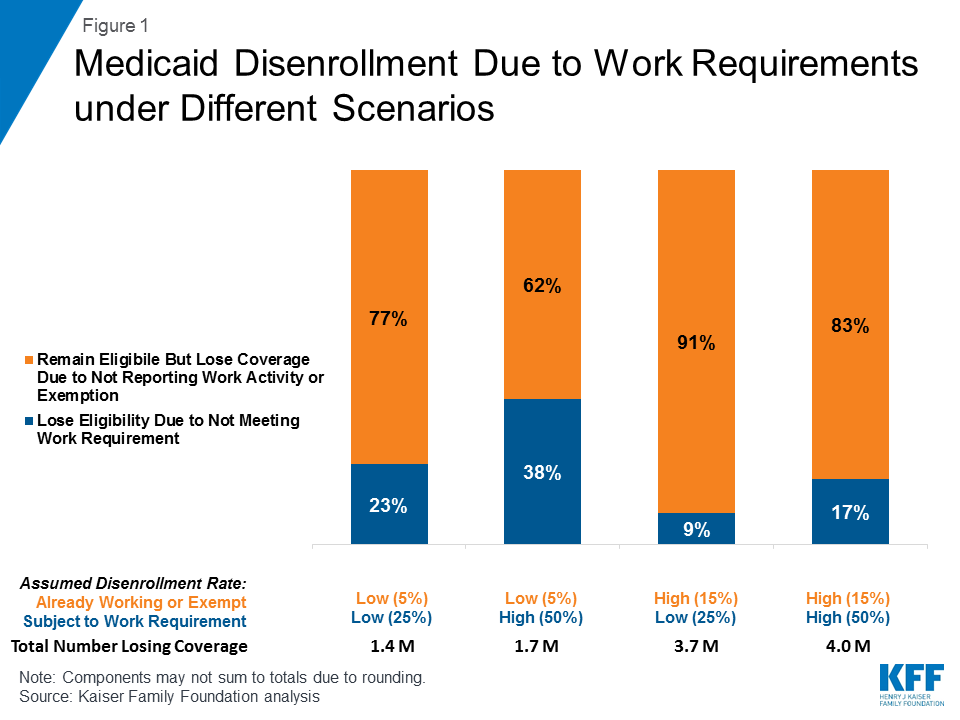

This analysis provides illustrative scenarios of potential nationwide reductions in Medicaid coverage if all states implemented work requirements similar to those currently proposed. The scenarios assume low and high disenrollment rates tied to compliance with the work requirements and related problems with reporting, based on disenrollment rates reported in existing studies of the effect of Medicaid reporting requirements and state estimates of enrollment under proposed waivers. Overall, among the 23.5 million non-SSI, non-dual, nonelderly Medicaid adults, disenrollment ranges from 1.4 million to 4.0 million under the scenarios considered (Figure 1). Because the majority of Medicaid adults are already working or likely exempt from work requirements, they account for a large share of people losing coverage even if they may lose coverage at a lower rate than those who are not already working but subject to work requirements. Specifically, under all scenarios, most disenrollment would be among individuals who would remain eligible but lose coverage due to new administrative burdens or red tape versus those who would lose eligibility due to not meeting new work requirements.

Figure 1: Medicaid Disenrollment Due to Work Requirements under Different Scenarios

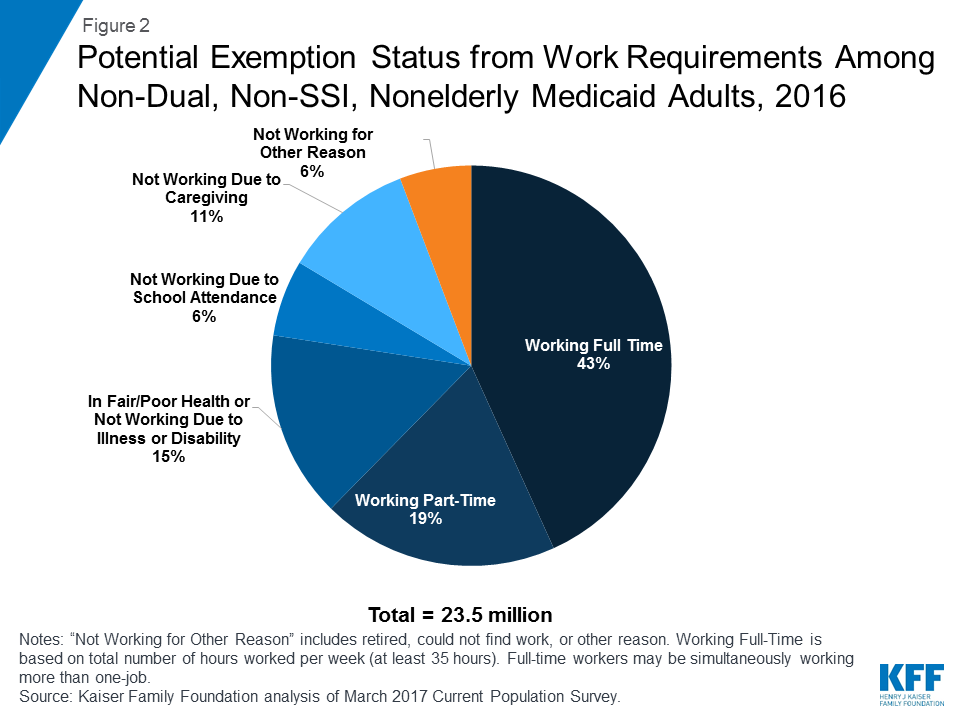

Earlier analysis shows that most nonelderly Medicaid adults already are working or face significant barriers to work, leaving a very small share of adults to whom these policies are directed. More than six in ten nonelderly, non-dual, non-SSI Medicaid adults are already working (Figure 2). Among those who are not working, most are in fair/poor health or report illness or disability, caregiving responsibilities, or going to school as reasons for not working. Many of these reasons would likely qualify as exemptions from work requirement policies. This would leave 6% of the population to whom work requirement policies could be directed. Some in this group report they are retired (2%), which often is related to ill health, and others in this group report that they are unable to find work (2%); just 1% are not working for another reason.

Figure 2: Potential Exemption Status from Work Requirements Among Non-Dual, Non-SSI, Nonelderly Medicaid Adults, 2016

However, work requirements have implications for all populations covered under these demonstrations. Those who are already working still must successfully document and verify their compliance. Those who qualify for an exemption also must successfully document and verify their exempt status, as often as monthly.

States will need to develop reporting and verification systems to administer work requirements. In most cases, these systems will require enrollees to actively report participation in work or another qualifying activity or obtain an exemption from the requirement. For example, in Arkansas, enrollees must set up online accounts and log into their accounts by the 5th of each month to attest to participating in work or other qualifying activities.

To estimate potential coverage losses nationally if all states were to implement work requirements, we started with the analysis above of current work status and reasons for not working among the non-SSI, non-dual, nonelderly Medicaid adult population. We applied different assumptions about changes in coverage to three groups: those who are already working, those who are likely exempt, and those subject to new work requirements. Additional detail is available in the Methods appendix at the end of this brief.

Disenrollment among those who may still be eligible but experience challenges in complying with administrative reporting requirements may be considered an “unintended” negative consequence of implementing a policy. Research shows that administrative requirements in Medicaid create barriers for individuals to enroll and stay enrolled in coverage. These studies broadly investigate how many and why Medicaid and/or CHIP enrollees lost coverage despite evidence that they remain eligible for the program or how certain enrollment policy changes (such as adding or dropping reporting requirements) affected enrollment. While some may move off Medicaid due to increases in income or obtaining other coverage, many who are eligible may lose coverage for failure to return or misdirected paperwork or other necessary documentation or for failure to pay premiums. These studies can be a good proxy for attempting to understand how new administrative requirements such as obtaining an exemption or verifying work status might affect enrollment. Based on our review of numerous studies, we applied a “low” disenrollment rate of 5% and a “high” of 15% among the population likely exempt from work requirements or already working.

We classified as likely subject to the work requirement anyone who reported the reason they were not working was that they were not able to find work, retired, or other reason. We reviewed state estimates of enrollment effects of imposing work requirements in Medicaid and research examining disenrollment due to the imposition of work requirements in TANF and SNAP to develop disenrollment rates among those subject to work requirement. The studies we reviewed estimated a broad range of disenrollment rates. Based on this information, we assumed a “low” disenrollment rate of 25% and a “high” rate of 50% among people likely not exempt from work requirements.

Overall, among the 23.5 million non-dual, non-SSI, nonelderly Medicaid adults, disenrollment ranges from 1.4 million to 4.0 million under the illustrative scenarios considered. These totals are highly subject to the assumed disenrollment rates. They represent a range of 6-17% enrollment loss among the non-SSI, non-dual, nonelderly Medicaid population and a range of 3-6% enrollment loss among the total Medicaid population.

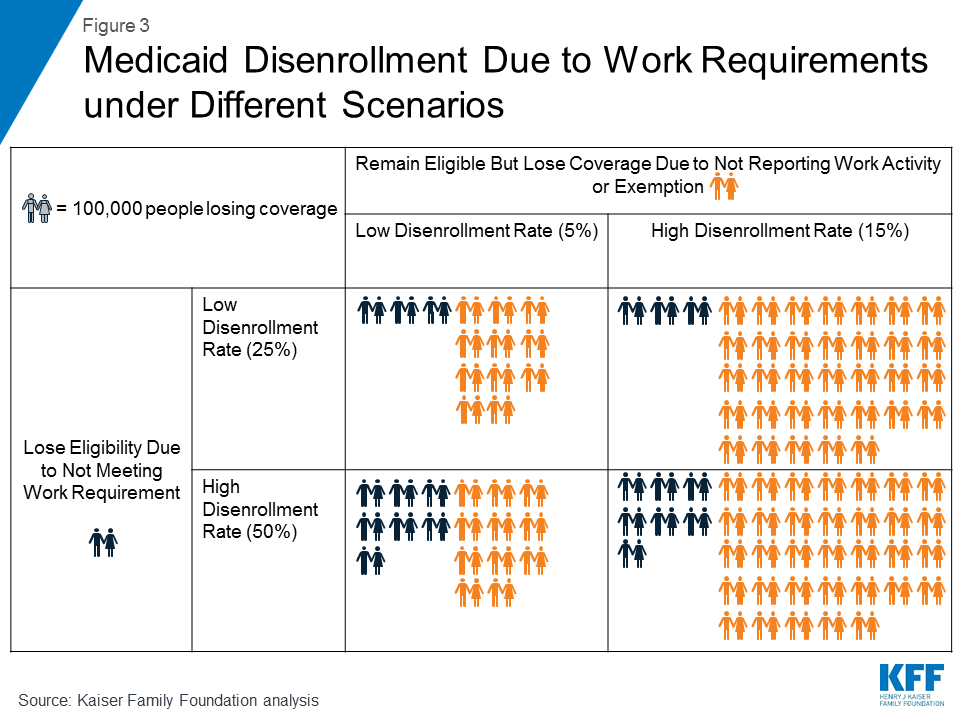

In all scenarios, most people losing coverage are disenrolled due to lack of reporting rather than not complying with the work requirement (Figure 3). Because the majority of Medicaid adults are already working or exempt, they account for most people losing coverage even though they lose coverage at a lower rate than those not working and subject to the new requirement. Even in the scenario that uses a “low” disenrollment rate among the exempt/working population and a “high” disenrollment rate among those subject to the requirement, 62% of those losing coverage are in the exempt/working category.

Figure 3: Medicaid Disenrollment Due to Work Requirements under Different Scenarios

The structure of state waiver requests typically targets so-called “able-bodied” adults for work requirements, exempting those who are parents, students, or medically frail. However, even those exempt from work requirements may still have to document their exemption status, creating new paperwork or reporting obligations for them, and adults who are already working also will have to document and report their hours. There is a risk of eligible people losing coverage due to their inability to navigate these processes, miscommunication, or other breakdowns in the administrative process. Drawing on literature showing disenrollment due to administrative requirements in Medicaid, this analysis shows that, under all scenarios considered, most people losing coverage would actually be exempt from or complying with work requirements, an outcome that may be considered an unintended negative consequence of these programs. Given limited availability of other coverage options for low-income individuals, most people losing Medicaid coverage are likely to become uninsured, which may be particularly problematic for the large share of Medicaid adults with health problems.

Potential loss of Medicaid among eligible enrollees highlights how work requirement programs might undo progress in helping eligible individuals access Medicaid coverage and could return Medicaid to welfare rules. In recent decades, as Medicaid has “de-linked” from cash assistance and developed into a health coverage program for low-income individuals without access to other coverage, states have implemented enrollment and renewal simplification measures to streamline Medicaid administration and make gaining and keeping coverage easier for eligible individuals. Increased documentation requirements stemming from work requirement waivers could reverse these changes and shift Medicaid from a health insurance program for low-income families back to one that operates under welfare rules.

New requirements will increase administrative costs, complexity and potential coverage losses among those who remain eligible. States implementing work requirements will likely have to design new systems to reflect changes in eligibility rules, to enable enrollees to report compliance, to interface with other programs (such as SNAP, TANF, or employment training), to implement coverage lock-out periods, and to exchange eligibility information among the state, enrollment broker, health plans, and providers. New staff may be required to conduct beneficiary education, develop notices, evaluate and process exemptions, and review more applications as churn increases and enrollees appeal coverage lockout periods. These fundamental changes to Medicaid administration may lead to even greater coverage losses than literature on past reporting requirements finds, as that literature is based on more incremental changes to Medicaid administration (e.g., changing the time frame required for renewal). In addition, how well states administratively operationalize these policy changes will affect the magnitude of the enrollment effect. States that face enrollment declines will face loss of federal matching funds for those enrollees (at enhanced federal matching rates for those eligible under the ACA), potentially creating a situation in which states are faced with either spending more on administration or losing federal Medicaid funds.

Because work requirement programs may disproportionately affect certain groups of enrollees, disenrollment could be concentrated among particularly vulnerable populations. Analyses show that older adults, people with disabilities, and women have lower rates of work than other groups and may face particular challenges in meeting exemptions or navigating exemption policies. In addition, analysis of proposed legislation in Michigan to impose work requirements—but exempt individuals in counties with unemployment exceeding 8.5 percent—showed that the policy would have disparate racial impact and would disproportionately exempt whites in more rural areas compared to blacks in more urban areas. 2 This provision was not included in the legislation adopted in Michigan, but waivers approved in other states require states to assess and determine if exemptions or other program changes are needed for certain geographic areas (e.g., places with high unemployment, limited economic or educational opportunities, lack of public transportation) to prevent work requirement programs from being impossible or unreasonably burdensome to meet. Depending on how these exemptions are designed and implemented, they could have disproportionate effects on some groups of beneficiaries.

Restrictions on state use of Medicaid funds under waivers will limit how many non-workers may be able to comply with new requirements. The CMS guidance on work requirements is explicit that states will be required to describe strategies to assist beneficiaries in meeting work requirements but may not use federal Medicaid funds for supportive services to help people overcome barriers to work. It is unclear how states will come up with the additional funds needed to address successfully the multiple barriers (childcare, transportation, education, training, etc.) that interfere with the ability to work. As experience with TANF shows, without sufficient support systems and services, people subject to work requirements may face challenges in finding and retaining employment.