One third of those who have won a case against the UK at the European human right court were terrorists, criminals or prisoners.

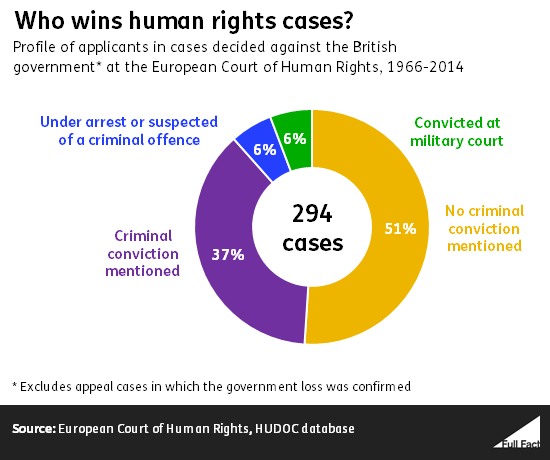

Around half of successful cases involved someone convicted or suspected of a criminal offence at some point. The answer depends on how you define "criminal".

"A third of those who have won against Britain at the European Court of Human Rights are terrorists, prisoners or criminals, figures show."

The Sun, 15 August 2015

Terrorists, criminals and prisoners are people too, at least in the eyes of human rights law. Anyone can apply to the European Court of Human Rights for a declaration that their rights have been breached; what they might have done in the past isn't relevant to whether or not they have a case.

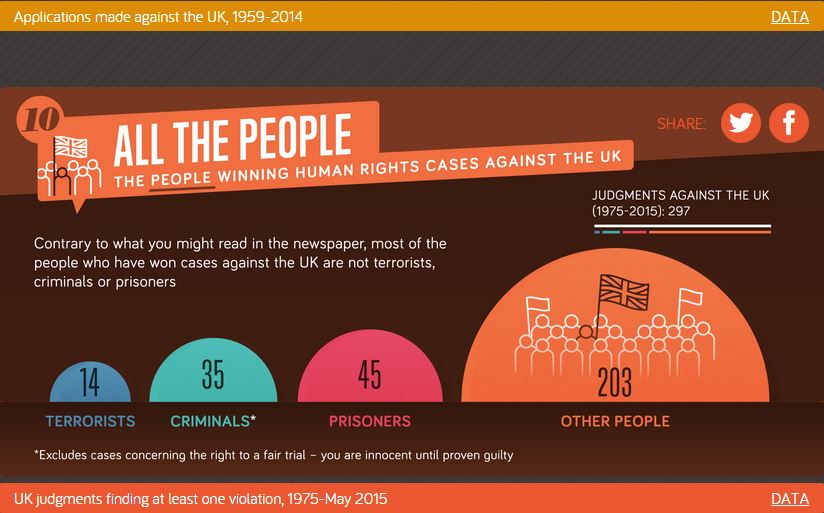

The figure of one third of those successful at the Court being a criminal, terrorist or prisoner comes from the human rights organisation RightsInfo. It says that of the 297 judgments where the Court has found that the British government had violated someone's rights, 203 haven't involved anyone of that background.

We make that figure 150—so just under half the cases involved someone convicted or suspected of a criminal offence. But the answer very much depends on what you mean by "criminal".

Who counts as a criminal?

In the chart below, we define criminals or suspects widely. We've included anyone who's ever been convicted of a criminal offence, according to the Court's judgment in their human rights case. This includes terrorism suspects with prior convictions, a man hit with financial penalties for non-payment of tax and a woman cautioned for abducting her grandson.

RightsInfo, as we can see from the source data it helpfully publishes, doesn't include cases like these in its list of "terrorists", "criminals" and "prisoners".

More fundamentally, it excludes around 30 other cases where it's not in dispute that the applicant committed a criminal offence. This is because the case wasn't about their status as a criminal, or because the Court went on to find a problem with their conviction under article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

This protects the right to a fair trial. You would expect to find people convicted of a crime, in circumstances they consider unfair, to rely on this article before the Court. In that sense, "criminals" applying to the Court is what's supposed to happen.

This choice not to count some people convicted of offences as "criminals" accounts for most of the differences in our figures: we've included every mention of past criminality, whether or not it was relevant to the case or deemed a human rights violation by the Court.

RightsInfo told us that "it makes more sense to exclude those claims from the 'criminal' category where the fact of the criminal conviction is irrelevant to the nature of the claim".

Instead, it deems a person "criminal" only where their criminal status was central to the case, but the court's finding of a human rights violation didn't affect their status as a criminal.

No hard and fast rules on who counts as a "criminal", but criminal conviction the easiest guide

If by "criminal" you mean anyone who has ever committed a criminal offence, and you want to know how many of those people have ever won at the European Court of Human Rights, then our chart answers your question.

If you think not everyone convicted of an offence should be labelled as a "criminal", you'll prefer RightsInfo's more selective approach. But you can run into problems when you start to pick and choose among people with a criminal record who you call a "criminal" and who you don't. This leads to inconsistencies, as well as conclusions that seem at odds with common understandings of the term.

Hard cases

Take the case of a man convicted of importing heroin, who we've categorised as a "criminal". The Court found that his right to privacy had been breached by unlawful surveillance used at his trial, although it didn't affect the fairness of the conviction. RightsInfo says he counts as a non-criminal "other person" because the Court's decision wasn't about his status as a criminal: he could have won his human rights case even if found not guilty.

RightsInfo labels the child killers of James Bulger as "criminals", whereas Raphael Rowe and Michael Davis are "other people". In both cases, the people involved had been convicted of murder at the time they applied to the Court, which in both cases found the same thing: that the applicants' right to a fair trial had been breached. (The murder convictions of Mr Rowe and Mr Davis were, in addition, subsequently quashed by the Court of Appeal back in England.)

These kinds of difficulties are why we've gone for a more black-and-white approach.

There's no perfect numerical answer to the question of criminals winning cases against the British government at the European Court of Human Rights. What we can say is that in assessing the proportion connected to criminality, half represents the highest reasonable figure, and one third the lowest possible.

Update 11 September 2015

We added that some cases won by "criminals" concern the right to a fair trial, the existence of which means that some cases heard by the Court will invariably involve people convicted of a criminal offence.